#Expert – Blog series: How to create a gender-just healthy planet

by Dr. Jutta Emig

For our work on international chemicals and waste management, it is essential that we pay attention to women and gender issues. The gender actions developed by the BRS Conventions secretariat are an important step towards developing comprehensive gender strategies and taking effective institutional measures. This and other policy actions and instruments could serve as suggestions to create a gender-just framework for a sound management of chemicals and waste beyond 2020. One important instrument are Gender Impacts Assessments, and I would like to share the experience with the Gender Impact Assessment (GIA) developed in the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) and share some aspects of ongoing work on gender and environment issues.

BMU developed its GIA model in 2004, in collaboration with the Institute for Social-Ecological Research (ISOE). GIA is a key instrument of the political strategy of gender mainstreaming, originally developed in the Netherlands in the early Nineties (Verloo/Roggeband 1996). It is an ex ante evaluation or analysis of a law, policy or programme that makes it possible to determine, in a preventative manner, if its future implementation “is causing negative consequences for the state of equality between women and men” (EIGE 2018). The basic understanding of GIA is “that the gender neutrality of political measures often has unintentional but highly consequential and often negative impacts on gender relations in a society and on men and women themselves” (ISOE 2002). Thus, the central question of GIA is: “Does a policy measure reduce, maintain or increase the gender inequalities between women and men?” (EIGE 2018).

GIA Stage Model

The environmental Gender Impact Assessment developed by BMU and ISOE is the specific review of an environmental policy measure by using a GIA stage model. Its three stages are:

- Relevance (Pre Test): In the first step it is checked whetherthe implementation of a GIA is relevant to the examined policy measure or not. Are persons directly or indirectly affected by the measure or parts of it and to what extend? At the end of this step, the decision is made if a GIA should be implemented or not. At the end of this step, the decision is made if a GIA should be implemented or not.

- Gender Impact Analysis (Main Test): In the second step, the gender

impacts are analyzed. Which factors of the policy measure are influencing women and men, as well as gender relations? The aim of this working step is to provide a detailed description of relevant gender aspects of the examined policy measure that will lay the foundations for the subsequent rating. - Rating and Voting: In the third step, the analyzed gender impacts are evaluated and improvements are developed. At the end these are again tested: Are gender aspects sufficiently taken into account within the new recommendations? Is gender equality better addressed by the measure than before the measure?

Last but not least, the GIA stage model has to be anchored in the regular work. In Germany, a Gender Focal Point at the Federal Environment Agency is managing the work on gender and environment issues and within the research project “The contribution of gender justice to successful climate politics”, the Federal Environmental Agency is currently further developing the GIA instrument and adapting it to issues related to climate change.

In this context, the dimensions of gender analysis are being further developed, including with a view to the transformative potential of gender mainstreaming in all sustainable development policies. In a current research project on gender and climate change (Röhr, Alber & Göldner 2017) existing gender dimensions of such an analysis were harmonized and further developed. Seven provisional gender dimensions were identified (ibid.):

- Care economy / care work (sex specific responsibilities for work and decisions inside the house and household; cost-benefit-analysis of care; logic and criteria of the care economy)

- Income economy / paid work (sex-specific division of labour of paid and unpaid work; gender pay gap; poverty and poverty risks; distribution of wealth)

- Public resources: provision, design, access, usability of public services and infrastructures (distribution of public space, public finance, quantity and quality of services & infrastructures, access to resources)

- Structural aspects: symbolic order (dominant societal constructions of gender and gender identities, including perceptions, attitudes, risk assessments, and problem identification)

- Structural aspects: institutionalized andro-centrism (institutional rationalities that determine the understanding of tasks, processes, organization and outcome; models of masculinity as the norm, conceptualization, methods, production of knowledge)

- Power of definition and decision-making of actors (processes, decisions, power relations and governance structures, participation, empowerment, choice of instruments)

- Body, health, intimacy (physical differences between the sexes and age groups, sexual harassment, reproductive health, sex-specific responsibilities for health, sex-specific perception of physical risks)

These seven dimensions allow identifying differences between genders in terms of roles, identities and behavior that lead to differences in exposure and impact and to address root causes of inequities, injustice and unsustainable development.

Transformative potential of GIA

The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda clearly states that we need fundamental change: transformation of economies and societies towards justice, environmental protection, and resource-efficiency. Gender Equality is an essential cross-cutting task for advancing transformation towards sustainable development, justice and peace. GIA has enormous potential in this regard: beyond avoiding negative effects it can also be used in a transformative way as a tool for defining gender equality objectives and formulating policies that proactively promote gender equality.

Sex differences, and gender differences in terms of roles and identities are important to understand so that we can improve chemicals and waste management. But we can go a step further: We also need to understand structural causes of gender inequalities, environmental degradation and pollution. Gender injustices and gender inequalities are symptoms of androcentric structures in societies. Using GIA helps to see these connections and to find better solutions. A future framework for the sound management of chemicals and waste should use this potential and integrate GIA as a tool when developing chemicals and waste management policies.

References:

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2018): Homepage: http://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/methods-tools/gender-impact.

Institute for Social-Ecological Research (ISOE) (2002): Gender Impact Assessment in the Field of Radiation Protection and the Environment. Concluding Report.

Verloo, Mieke/Roggeband, Connie (1996): Gender Impact Assessment: The Development of a New Instrument in the Netherlands. In: Impact Assessment 14/996, 3-20.

Röhr, Ulrike/Alber, Gotelind/Göldner, Lisa (2017): The contribution of gender justice to successful climate politics: impact assessment, interdependencies with other social categories, methodological issues and options for shaping climate policy. Summary of the 1. Interim report (work package 1).

Author

Dr. Jutta Emig is Head of the Unit International Chemical Safety, Sustainable Chemistry at the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety and headed the ministerial project team for the development of GIA.

The HLPF itself concluded by adopting a negotiated, but not legally binding,

The HLPF itself concluded by adopting a negotiated, but not legally binding,

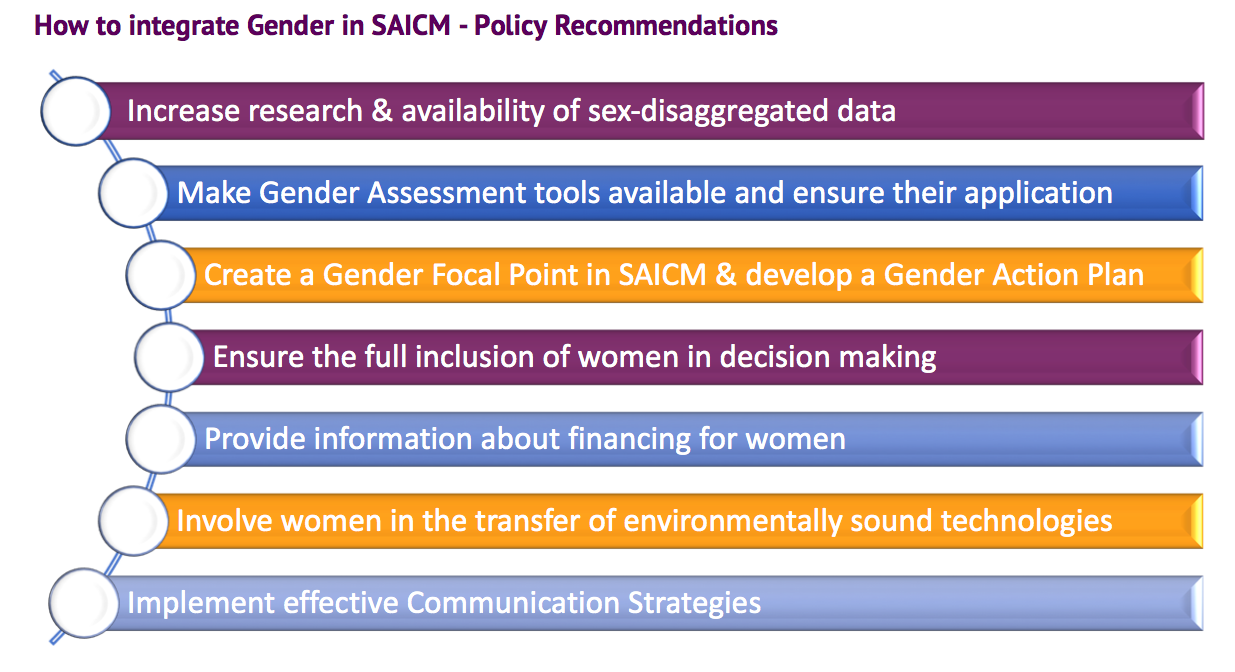

sex-disaggregated data, analyze gender roles and identities and how they impact our interactions with chemicals and waste along the whole life cycle. But how to go about that?

sex-disaggregated data, analyze gender roles and identities and how they impact our interactions with chemicals and waste along the whole life cycle. But how to go about that?

With the year 2020 fast approaching, Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) and its stakeholders are currently

With the year 2020 fast approaching, Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) and its stakeholders are currently