Expert – Blog Series: How to create a gender-just healthy planet

by Halshka Graczyk – International Labour Organization (ILO)

Recognising diversity, including gender differences at the workplace, is critical for protecting the health and safety of workers, particularly when it comes to hazardous exposures from chemical substances. A number of social as well as biological factors impact the effect that chemicals have on worker health and safety. Not only may exposure scenarios be different depending on factors related to gender, the impact of exposure may be different dependent on biological sex characteristics.

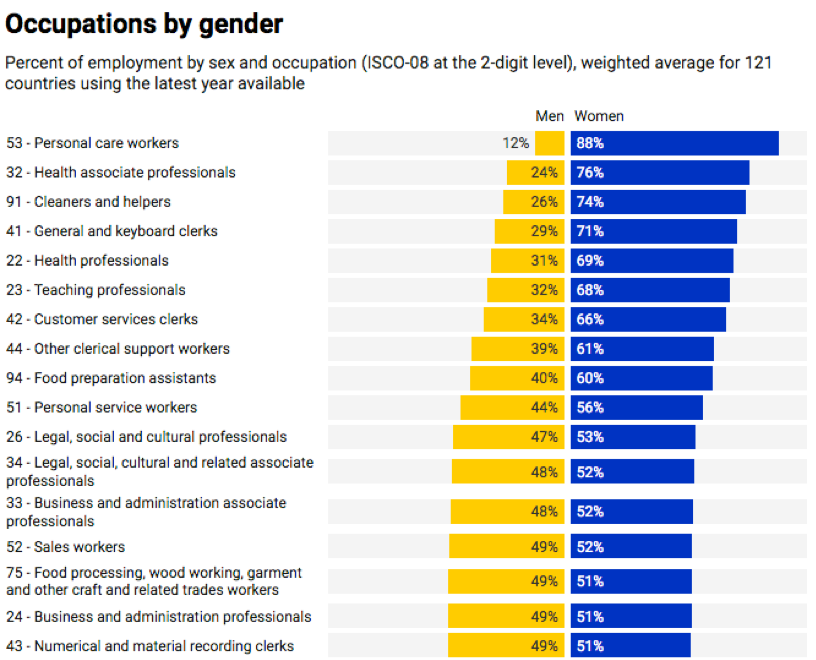

In regards to exposures, owing to differences in social and occupational roles, and prevailing harmful stereotypes, women, men and persons with diverse gender identities[1] face different exposure scenarios in regards to the chemicals encountered and the magnitude and duration of exposure. Recent ILO estimates reveal that female workers constitute the majority of the workforce in specific occupations, ones that may face increased exposures to chemicals, such health professionals; cleaners; and food processing, wood working, garment and craft workers (Figure 1). Female workers in the garment sector for example are disproportionately exposed to a number of hazardous dyes and solvents, some of which are proven carcinogens, as well as endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Unfortunately, work predominantly undertaken by women is often presumed to be less hazardous than that undertaken by men, and may consequently receive less attention for critical workplace procedures, such as risk assessment, or worker training. In addition, work tools and personal protective equipment (PPE) have been traditionally designed for the Western male body. Tools and PPE with poor fit can lead to reduced protection and increase the risk of chemical exposure and accidents. In some cases, workers with poor fitting PPE may forgo using it at all. Female workers entering traditionally male jobs in areas like construction, laboratory work and emergency services are particularly at risk from inappropriately designed PPE.

When it comes to decision making at work, women may be less likely to be heads of operations and therefore have less decision-making power when it comes to hazardous exposures. Women are also less likely than men to be unionized and have high-level positions in workers organizations’ and less likely to participate in OSH committees.[i]

In regards to health effects, it is well evidenced that biological differences between sexes, such as physiological, chromosomal, and hormonal differences, create differing susceptibilities to the effects of toxic chemicals. Female workers are at particularly high risk during child bearing years and pregnancy, when even low-doses of chemicals might elicit dramatic and irreversible effects. This is particularly relevant for endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that are able to induce hormonal effects at extremely low dosages, affecting fertility, fecundity and fetal development.

In addition, females are more likely to have more adipose tissue and to store chemicals that bioaccumulate, such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals like mercury. Female workers exposed to mercury in artisanal mining, in the dismantling of e-waste, or other sectors, may face severe consequences to their reproductive health, and exposure during pregnancy may result in spontaneous abortion, neurobehavioral consequences, or birth defects. The fact that mercury can bioaccumulate means that occupational exposures even years before pregnancy can still negatively affect the developing fetus.

Recent data shows that occupational cancers represent an important and growing cause for work-related deaths. While many occupational studies do not report gender disaggregated data, those that do cite an alarming trend of increased cancer rates in female workers exposed to chemicals, namely within rubber and plastics production, and in jobs involving exposures to solvents, dusts, heavy metals, and pesticides. A different cellular response to oxidative stress between men and women in cancer susceptibility has been hypothesized, raising the question of whether the classification of occupational carcinogens should be gender specific.[ii]

However it is essential to note that biological susceptibility should never be used as an excuse to discriminate against workers entering a job; instead jobs or tasks must be accommodated to protect workers’ health.

Despite evidence for gender-based differences when it comes to OSH and chemicals, it is clear that we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg. Occupational health research for female workers has focused on limited sectors. Very few physiological or toxicological studies have been carried out on chemical exposures, and the studies for gender diverse persons are virtually non-existent. Moreover, women’s occupational illnesses are often under-diagnosed, under-reported and under-compensated compared with men’s, making it difficult to extrapolate from occupational disease registries.[iii]

ILO role and response

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) was founded on the concept of guaranteeing protection for the life and health of all workers in all occupations, including workers exposed to hazardous chemicals. As such, the ILO has adopted more than 50 legal instruments on the protection of workers from chemical hazards, including Conventions, their accompanying Recommendations, and Codes of Practice. These legal instruments refer to “all workers” ensuring that all persons are protected from chemical hazards, in the workplace as well as in the wider community.

In addition to chemical instruments, the ILO Maternity Protection Convention (No. 183) sets out that pregnant women should not be obliged to carry out work that is a significant risk to her health and safety or that of her child. It outlines the need for the elimination of any workplace risk, additional paid leave to avoid exposure if the risk cannot be eliminated, and the right to return to her job or an equivalent job as soon as it is safe for her to do so. The accompanying Recommendation (No.191) provides for specific risk assessment and management of risks concerning pregnant women, including exposure to biological, chemical or physical agents which represent a reproductive hazard.

The ILO has also developed Guidelines for Gender Mainstreaming in Occupational Safety and Health to assist policy-makers and practitioners in taking a gender-sensitive approach for the development and implementation of OSH policy and practice. In taking a gender sensitive approach, one recognizes that because of different jobs that men and women participate in, and the different societal roles, expectations and responsibilities they have, they may face unique chemical exposure scenarios, thus requiring appropriately designed control measures. This approach improves the understanding that gender-based division of labour, biological differences, employment patterns, social roles and structures all contribute to gender-specific patterns of hazardous exposures.

Chemical safety at the workplace can no longer afford to be gender-blind. Unless we begin to recognize, respect and address gender diversity at work, and develop inclusive and responsive gender-sensitive OSH policies and practice, we will never be able to fully protect workers, their families and their communities from the scourge of hazardous chemical exposures that continue to occur worldwide.

[1] Gender identity may or may not correspond with the biological sex assigned, and should rather be understood as the individual personal experience of gender. Gender identity exists on a spectrum and is not necessarily confined to completely male or completely female. While the terms “women,” “men,” “female” and “male” are used here to describe research findings, gender diversity encompasses persons of all gender identities and/or expressions.

[i] ILO (2013). https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/resources-library/publications/WCMS_324653/lang–en/index.htm

[ii] Ali I, Högberg J, Hsieh JH, Auerbach S, Korhonen A, Stenius U, Silins I. Gender differences in cancer susceptibility: role of oxidative stress. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:985–992. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw076.

[iii] ILO (2013). https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/resources-library/publications/WCMS_324653/lang–en/index.htm

2 Replies to “Chemical safety at work: What’s gender got to do with it?”